Seven Against Thebes

| Seven against Thebes | |

|---|---|

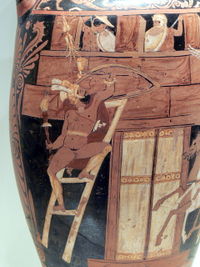

Scene from the Seven against Thebes: Capaneus scales the city wall of Thebes, Campanian red-figure amphora, ca. 340 BC, Getty Villa (92.AE.86) |

|

| Written by | Aeschylus |

| Chorus | Theban Women |

| Characters | Eteocles Antigone Ismene Messenger |

| Setting | Citadel of Thebes |

The Seven against Thebes (Greek: Ἑπτά ἐπί Θήβας, Hepta epi Thēbas) is the third play in an Oedipus-themed trilogy produced by Aeschylus in 467 BC. It concerns the battle between an Argive army led by Polynices and the army of Thebes led by Eteocles and his supporters. The trilogy won the first prize at the City Dionysia. Its first two plays, Laius and Oedipus as well as the satyr play Sphinx are no longer extant.

Contents |

Plot summary

When Oedipus, king of Thebes, realized he had married his own mother and had four children with her, he blinded himself and cursed his sons to divide their inheritance (the kingdom) by the sword. The two sons, Eteocles and Polynices, in order to avoid bloodshed, agreed to rule Thebes in alternate years. After the first year, Eteocles refused to step down and as a result, Polynices raised an army (captained by the eponymous Seven) to take Thebes by force. This is where Aeschylus' tragedy starts. There is little plot as such; instead, the bulk of the play consists of rich dialogues that show how the citizens of Thebes feel about the threat of the hostile army before their gates, and also how their king Eteocles feels and thinks about it. Dialogues also show aspects of Eteocles character. There is also a lengthy description of each of the seven captains that lead the Argive army against the seven gates of the city of Thebes as well as the devices on their respective shields. Eteocles, in turn, announces which Theban commander he will send against each Argive attacker. Finally, the commander of the troops before the seventh gate is revealed to be Polynices, the brother of the king. Then Eteocles remembers and refers to the curse of their father Oedipus[1] King Eteocles resolves to meet and fight his brother in person before the seventh gate and exits. Following a choral ode, a messenger enters, announcing that Eteocles and Polynices have killed each other in battle. Their bodies are brought on stage, and the chorus mourns them.

Due to the popularity of Sophocles's Antigone, the ending of Seven against Thebes was rewritten about fifty years after Aeschylus' death.[2] Where the play was meant to end with somber mourning for the dead brothers, it instead contains an ending that serves as a lead-in of sorts to Sophocles' play: a messenger appears, announcing a prohibition against burying Polynices; Antigone, however, announces her intention to defy this edict.

The mythic content

The mytheme of the "outlandish" and "savage" Seven who threatened the city has traditionally seemed to be based on Bronze Age history in the generation before the Trojan War,[3] when in the Iliad's Catalogue of Ships only the remnant Hypothebai subsists on the ruins. Yet archaeologists have been hard put to locate seven gates in "seven-gated Thebes":[4]In 1891 Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff declared that the seven gates existed only for symmetry with the seven assailants, whose very names vary: some have their own identity, like Amphiaraus the seer, "who had his sanctuary and his cult afterwards... Others appear as stock figures to fill out the list," Burkert remarks. "To call one of them Eteoklos, vis-à-vis Eteokles the brother of Polyneikes, appears to be the almost desperate invention of a faltering poet"[5] Burkert follows a suggestion made by Ernest Howald in 1939 that the Seven are pure myth led by Adrastos (the "inescapable") on his magic horse, seven demons of the Underworld; Burkert draws parallels in an Akkadian epic text, the story of Erra the plague god, and the Seven (Sibitti), called upon to destroy mankind, but who withdraw from Babylon at the last. The city is saved when the brothers simultaneously run each other through. Burkert adduces a ninth-century relief from Tell Halaf which would exactly illustrate a text from II Samuel 7: "But each seized his opponent by the forelock and thrust his sword into his side so that all fell together".

The mythic theme passed into Etruscan culture: a fifth-century bronze mirrorback[6] is inscribed with Fulnice (Polynices) and Evtucle (Eteocles) running at one another with drawn swords. A particularly gruesome detail from the battle, in which Tydeus gnawed on the living brain of Melanippos in the course of the siege, also appears, in a sculpted terracotta relief from a temple at Pyrgi, ca. 470-460 BC.[7]

The Seven Against Thebes were

- Adrastus

- Amphiaraus

- Capaneus

- Hippomedon

- Parthenopeus

- Polynices

- Tydeus

Allies:

- Eteoclus and Mecisteus. Some sources, however, state that Eteoclus and Mecisteus were in fact two of the seven, and that Tydeus and Polynices were allies. This is because both Tydeus and Polynices were foreigners. However, Polynices was the cause of the entire conflict, and Tydeus performed acts of valour far surpassing Eteoclus and Mecisteus. Either way, all nine men were present (and killed) in the battle, save Adrastus.

The defenders of Thebes included

- Melanthipus

- Polyphontes

- Megareus

- Melanippus

- Hyperbius

- Actor

- Lasthenes

- Eteocles

See also Epigoni, the mythic theme of the Second War of Thebes

Notes

- ↑ Eteocles simply mentions a curse, which the chorus state in full at 785ff.

- ↑ Aeschylus. Prometheus Bound, The Suppliants, Seven Against Thebes, The Persians. Philip Vellacott's Introduction, pp.7-19. Penguin Classics.

- ↑ "There is no reason to suppose that the tale was not based on historical fact" Cambridge Ancient History II (1978:168), noted by Burkert 1992:107n.

- ↑ Burkert 1993:107-08 briefly surveys the attempts, with bibliography.

- ↑ Burkert 1993:108.

- ↑ Illustrated in Larissa Bonfante and Judith Swaddling, Etruscan Myths (Series The Legendary Past, University of Texas/ British Museum) 2006, fig. 9 p. 22.

- ↑ Relief in the Museo Etrusco, Villa Giulia, Rome, illustrated in Bonfante and Swaddling, fig. 10 p. 23, and p. 58.

References

- Burkert, Walter 1992. The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early Archaic Age "Seven against Thebes" pp 106-14. Burkert draws parallels between Greek and Ancient Near Eastern materials. Notes and bibliography.

Translations

- A. S. Way, 1906 - verse

- E. D. A. Morshead, 1908 - verse: on-line text

- G. M. Cookson, 1922 - verse

- Herbert Weir Smyth, 1922 - prose: full text

- David Grene, 1956 - verse

- Philip Vellacott, 1961 - verse

- Will Power, 2001 - verse, lyric

- George Theodoridis,2010, prose. full text:[1]

|

|||||||